We are going through a sermon series at church discussing different worldviews. Many people in our culture believe that faith and science are opposed to one another. They see them as either mutually exclusive or even incompatible. I want to argue that that they are not only compatible, but they are locked together in a logical sequence. In this essay, I will argue that modern scientific inquiry was built on top of the doctrines of Christian Theism.

Dr. Rebekah McLaughlin in her excellent book “Confronting Christianity”[1] points out that Dr. Hans Halvorson who is a professor of philosophy at Princeton, argues that not only did Christians throughout history invent science, but the reason they invented science was because they saw in the Scriptures a Creator God who is both rational and free.[2] In other words, when they looked around, they saw a God who provided order and who created principles or laws which govern the universe, such that we as His creatures might be able to discern these things. They believed nature was uniform and could be trusted to behave in predictable ways. But, since God is free, He could do this however He wanted to. Therefore, the only way to find out what those underlying rules are, is to “go and look.”

What the history of science suggests is that science assumes the existence of natural laws and presupposes the constancy of nature, but on what basis? I assert these assumptions of science stand on the foundation of Theism. Christians believe that God is unchanging (Mal 3:6) and that He governs nature by fixed patterns. (Gen 8:22) We believe He has entrusted us with stewardship and responsibility and given us language, senses and reasoning to live in His world. One intertestamental writer said it this way, “Thou hast ordered all things in measure and number and weight” (Wisdom of Solomon 11.20). To do science (as Johannes Kepler said) is to “think God’s thoughts after Him.” The scientific achievements of Isaac Newton (1642-1727) were summarized in poet Alexander Pope’s famous couplet:

“Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night

God said: ‘Let Newton be!” and all was light.”

Pope’s point is clear, that Newton discovered some of the fundamental laws of nature as given by God. Research professor Peter Harrison writes,

“What is often less appreciated, however, is that part of the novelty of Newton’s achievement lay in his conviction that there were laws of nature there in the first place, awaiting discovery…This idea – laws of nature in the scientific sense – was an innovation of the seventeenth century and was a consequence of the extension of God’s legislative moral power to the physical world. One of the pioneers of this new understanding of laws of nature was the French philosopher and scientist Rene Descartes (1596-1650), who wrote that “God alone is the author of all the motions in the world. Descartes thus argued that because these laws had their source in an eternal and unchanging God, the laws of nature must themselves be eternal and unchanging. Descartes also set out a law of the conservation of motion, again arguing for it on the basis of God’s immutability. This idea that nature was governed by constant and immutable principles was an important precondition for experimental science…Robert Boyle, the father of modern chemistry and author of the eponymous law, observed that God’s creation operates according to fixed laws “which He alone at first established.” God’s authorship of the laws of nature guaranteed their universality and unchanging nature.” [3]

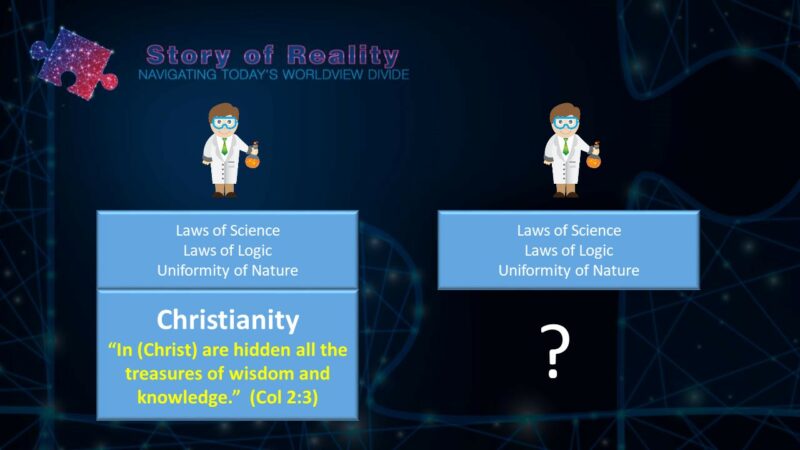

The problem (for the secular scientist) is that science itself is based on these inherently Christian presuppositions. In other words, science is only possible because of the assumption that an unchanging God upholds the universe in this logical, orderly way. This same God made our minds able to think and reason logically. We assume nature’s laws (such as the law of gravity) and the laws of logic (such as the law of non-contradiction), but without God, people do so without accounting for them.

In other words, without a belief in God, we run into what’s called in philosophy the “problem of induction.” This problem asks the following questions: 1) What are the justifications, if any, for any knowledge beyond our mere observations? 2) How can anyone generalize based on a number of finite observations? 3) On what basis can we assume that the future will occur as it always has in the past? Philosopher David Hume argued that our reason alone cannot even establish the grounds of proving cause and effect. Hume presented this problem of induction in his work “A Treatise of Human Nature,” writing this:

“There can be no demonstrative arguments to prove, that those instances, of which we have had no experience, resemble those, of which we have had experience.”[4]

Where can we go to determine with any degree of certainty that empiricism (the reliance on the senses for information) is a trustworthy source of knowledge? And furthermore, where can we go to determine with any degree of certainty that rationalism (our ability to use logic and reason) is a verifiable source of knowledge? We are left with complete uncertainty without God’s promises. But this leaves us with a world in which no one can live consistently.

“If the foundations are destroyed, what can the righteous do?” (Ps 11:3, ESV)

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) is responsible for introducing the term “transcendental” to philosophical discussion. All of us, he argued, must concede that knowledge is possible. Or else, there is no point to any discussion or inquiry. Now, given that knowledge is possible, said Kant, we should ask what the conditions are that make knowledge possible. What must the world be like, and what must the workings of our minds be like, if human knowledge is to be possible? The Transcendental argument became a staple of the writings of the idealist school that followed Kant, and from there it made its way into Christian apologetics. James Orr (1844-1913) employed it. But the twentieth-century apologist who placed the most weight on the transcendental argument (which he sometimes called “reasoning by presupposition”) was Dr. Cornelius Van Til (1895-1987) of Westminster Seminary. He, along with many of his students (Dr. Greg Bahnsen, Dr. John Frame, Dr. Scoff Oliphant) argued for the truth of Christian Theism based on “the Transcendental Argument for God.” (T.A.G.) Van Til would say that only Christianity provides the necessary preconditions for rational and scientific thought. He maintained that Christian theism is the presupposition of all meaning, all rational significance, and all intelligible discourse. Even when someone argues against Christian theism, Van Til said, he presupposes it, for he presupposes that rational argument is possible and that truth can be conveyed through language. The non-Christian, then, in Van Til’s famous illustration, is like a child sitting on her father’s lap, slapping his face. She could not slap him unless he supported her. Similarly, the non-Christian cannot carry out his rebellion against God unless God makes that rebellion possible. Contradicting God assumes an intelligible universe and therefore a theistic one.[5] The sure proof that God exists, Van Til would argue, is that “without Him, you can’t prove anything.”[6] His proof of God was based on “the impossibility of the contrary.”

This does not mean that secular scientists cannot make observations, use reason and do science, they can. But, they can do so only because they too live in God’s trustworthy world. The transcendental argument simply means that they have no philosophical justification for doing science. In other words, when scientists presuppose the laws of nature being uniform, they are borrowing from the Christian worldview (truth that comes from outside of the worldview of naturalistic materialism) when making these assumptions.

Evidence of the necessity of these assumptions can be found in the Bible, such as in Proverbs 1:7, “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge.” And, “All the treasures of wisdom and knowledge are hidden in Christ.” (Col 2:3) The Bible does make this kind of radical claim, that creation not only implies, but presupposes God. We must start with God, lest we become fools. (Ps 14:1, Rom 1:18-25, 1 Cor 1:20) For God is the creator of all, and therefore the source of all meaning, order, and intelligibility. It is in Christ that all things hold together (Col. 1:17). So without him everything falls apart; nothing makes sense. Therefore, the Bible teaches that God is not a God who is reasoned to, rather He is THE God that we (as finite human beings), simply cannot reason without. Belief in this Creator God who has revealed Himself through special revelation and most clearly in the person of Jesus Christ serves as a firm foundation for all of life and for scientific inquiry.

C.S. Lewis once said, “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen: not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.”[7]

Everyone must start with assumptions when doing science, but only scientists from a Christian worldview have justification for doing so. Scientists who come from a Christian worldview can account for such knowledge and certainty based on the belief that God has revealed Himself as the trustworthy Creator and sustainer of all His creation. (Col 1:1-20)

(To learn more about these important worldview issues such as the relationship between science and faith, visit our sermon series webpage here.)

References:

Bahnsen, Greg, Always Ready: Directions for Defending the Faith (Atlanta: American Vision, 1996).

Frame, John, Apologetics to the Glory of God (Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R Publishing, 1994).

Frame, John, Cornelius Van Til (Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R Publishing, 1995).

Lewis, C.S. Mere Christianity. (New York: Macmillan, 1960).

McLaughlin, Rebecca. Confronting Christianity (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019),

Oliphant, Scott. Covenantal Apologetics (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2013).

Pratt, Richard. Every Thought Captive: A Study Manual for the Defense of Christian Truth (Phillipsburgh, NJ, P & R Publishing, 1979).

Kant, Immanuel, Critique of Pure Reason, abridged, ed., tr., int. by Norman Kemp Smith (N. Y.: 1958).

Van Til, Cornelius, The Defense of the Faith (Philadelphia: 1963).

Works Cited:

[1] McLaughlin, Rebecca. Confronting Christianity (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019), Ch. 7.

[2] Prof. Hans Halvorson, “Does the Universe Need God?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDwpTcSEjak Accessed July 14, 2021.

[3] Peter Harrison is a Research Professor at University of Queensland and a Senior Research Fellow at the Ian Ramsay Centre in Oxford, where for a number of years he was the Idreos Professor of Science and Religion. He has published many books on the history of science and is editor of The Cambridge Companion to Science and Religion. Quotation taken from https://www.abc.net.au/religion/christianity-and-the-rise-of-western-science/10100570 Accessed July 14, 2021.

[4] For more basic information about this philosophical problem, visit https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Problem_of_induction

[5] Van Til, Cornelius, The Defense of the Faith (Philadelphia: 1963).

[6] Van Til, Cornelius, The Defense of the Faith (Philadelphia: 1963).

[7] C.S. Lewis. Mere Christianity (New York: Macmillan, 1960).